Corona en de cijfers

-

anonymous9

Re: Corona en de cijfers

@CarpeNoctem,

Terwijl vele landen te maken krijgen met tweede golf, neemt aantal besmettingen in Zweden duidelijk af

Spek naar je bek

Terwijl vele landen te maken krijgen met tweede golf, neemt aantal besmettingen in Zweden duidelijk af

Spek naar je bek

Re: Corona en de cijfers

In Thailand in de provincie Chon buri al 100 dagen geen lokaal veroorzaakt geval meer, enkel import.

Verder zijn de cijfers van het land ook wel om hier jaloers op te zijn.

Spek naar mijn bek.

Verder zijn de cijfers van het land ook wel om hier jaloers op te zijn.

Spek naar mijn bek.

-

anonymous9

- CarpeNoctem

- Verbannen Gebruiker

- Berichten: 1264

- Lid geworden op: 05 jan 2014

Re: Corona en de cijfers

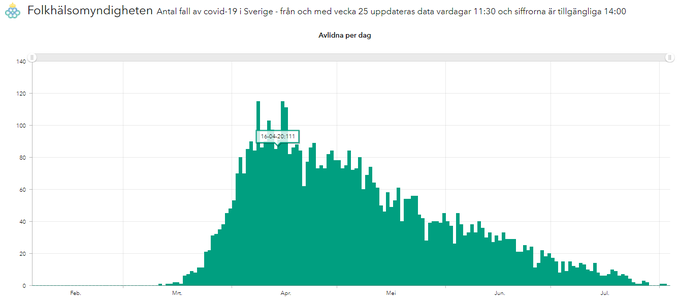

Bwa, ik hecht niet zo veel waarde aan die cijfers over het aantal besmettingen. Die cijfers hangen van te veel factoren af, en anderzijds zijn veel besmettingen behulpzaam in het bereiken van de groepsimmuniteit. Het enige cijfer dat echt van tel is is dat van het aantal doden.MoreOrLess schreef: ↑3 augustus 2020, 18:59 @CarpeNoctem,

Terwijl vele landen te maken krijgen met tweede golf, neemt aantal besmettingen in Zweden duidelijk af

Spek naar je bek

Kijk, een tijd geleden postte ene haelewyn hier:

waarop ik dit repliceerde:

Ondertussen geven de cijfers me gelijk. De laatste dagen vallen er bijna geen doden meer in Zweden.CarpeNoctem schreef: ↑20 juni 2020, 06:00Jouw kaartje toonde enkel dat er in week 22-23 meer gevallen werden vastgesteld in Zweden dan hier. We zijn ondertussen op het einde van week 25 en onze voorsprong op Zweden groeit nog steeds wat het aantal doden/inwoner betreft. Dus dat betekent dat die dekselse Zweden er beter in slagen die vele patiënten in leven te houden dan wij onze weinige. Als Zweden erin slaagt die patiënten in leven te houden slagen ze in hun opzet. De immuniteit ( of toch minstens de weerstand tegen) Covid-19 zal bij hen ondertussen verhoogd zijn zonder dat ze aan de hallucinante cijfers van ons komen.

Link

Anders Tegnell heeft (voorlopig?) over de ganse lijn gelijk gekregen. Veel minder doden dan bij ons en een hogere groepsimmuniteit.

Om nog maar te zwijgen over ordediensten die geen ridicule regels dienden op te leggen aan de burgers...

A government that robs Peter to pay Paul can always depend on the support of Paul.

Sorry to be a free speech absolutist. (© Elon Musk)

“I have never understood why it is "greed" to want to keep the money you have earned but not greed to want to take somebody else's money.” ― Thomas Sowell

Sorry to be a free speech absolutist. (© Elon Musk)

“I have never understood why it is "greed" to want to keep the money you have earned but not greed to want to take somebody else's money.” ― Thomas Sowell

Re: Corona en de cijfers

Je vergeet de volledige vergelijking te maken.

Landen als Thailand, China en Vietnam namen draconische maatregelen.

Zij zitten al een paar maanden rond 0 op een veel grotere bevolking dan de onze.

Zonder de theorieën van Anders Tegnell is het daar honderd keer beter gegaan. Geen groepsimmuniteit maar die hebben ze niet eens nodig gehad.

Daar valt meer te leren dan n Zweden.

Het aantal doden in Zweden, Nederland of België vergelijkend : daarbij is het resultaat niet alleen en niet rechtstreeks toe te schrijven aan 'geen maatregelen nemen'.

We hebben veel doden ondanks de maatregelen. Niet dankzij..

Wat zal in Zweden een tweede golf voorkomen ? Het is een echte vraag want ik ken hun huidige plannen daarvoor niet.

Voor mij heb je nog altijd gezwetst over de hele lijn en heel toevallig past er eens iets in je kraam. Dat is alles.

Neen. Niet het aantal doden alleen is van tel. Geen besmettingen is nog altijd beter dan veel besmettingen met weinig doden.

Vergelijk een auto die gemiddeld vier pannes per 30.000 km telt even niet met een die 2,8 pannes heeft. Leer iets van het merk dat 0,1 pannes heeft op 30.000 km.

Landen als Thailand, China en Vietnam namen draconische maatregelen.

Zij zitten al een paar maanden rond 0 op een veel grotere bevolking dan de onze.

Zonder de theorieën van Anders Tegnell is het daar honderd keer beter gegaan. Geen groepsimmuniteit maar die hebben ze niet eens nodig gehad.

Daar valt meer te leren dan n Zweden.

Het aantal doden in Zweden, Nederland of België vergelijkend : daarbij is het resultaat niet alleen en niet rechtstreeks toe te schrijven aan 'geen maatregelen nemen'.

We hebben veel doden ondanks de maatregelen. Niet dankzij..

Wat zal in Zweden een tweede golf voorkomen ? Het is een echte vraag want ik ken hun huidige plannen daarvoor niet.

Voor mij heb je nog altijd gezwetst over de hele lijn en heel toevallig past er eens iets in je kraam. Dat is alles.

Neen. Niet het aantal doden alleen is van tel. Geen besmettingen is nog altijd beter dan veel besmettingen met weinig doden.

Vergelijk een auto die gemiddeld vier pannes per 30.000 km telt even niet met een die 2,8 pannes heeft. Leer iets van het merk dat 0,1 pannes heeft op 30.000 km.

- CarpeNoctem

- Verbannen Gebruiker

- Berichten: 1264

- Lid geworden op: 05 jan 2014

Re: Corona en de cijfers

Nog niet nodig gehad bedoel je. Het valt af te wachten wat een volgende uitbraak brengt.

Lees hier eens een razend interessant interview met Anders Tegnell.

On the controversial question of immunity, he suggests that a larger percentage of the population in Sweden is already immune than antibody studies suggest.

“There are a number of small studies already that show that of people who had been diagnosed with Covid-19 with PCR, not all of them develop antibodies. On the other hand we have quite a lot of evidence that falling ill with Covid-19 twice seems to be extremely rare… Obviously there is also quite a big part of the population that has other kinds of immunity and T Cell immunity is the one that is most likely.

“What we see right now is a rapid fall in the number of cases, and of course some kind of immunity has to be involved in that as nothing else has changed. That means that immunity affects the R value quite a lot in Sweden today.”

Does that mean that Sweden will be better placed to limit second waves and future flare ups than countries that have had minimal infection levels so far?

“I think it’s likely that those kinds of outbreaks will be easier to limit in Sweden because there is immunity in the population. All our experience with measles and other diseases shows that … we know that with large immunity in the population it is much easier to control the outbreaks than if you don’t have immunity in the population.

“There is now a number of countries in Europe that have a fairly low level of spread for a very long time, which is very unusual with a disease that seems to be so contagious, and where there is so little immunity in the population. If that is really a sustainable way for the disease to exist we will wait and see — I think the fall will show if it is possible or not.”

Ik ga voor de auto die minst pannes heeft op 250.000 km. Want dat is wat er gebeurt, Zweden mikt op de lange termijn.

A government that robs Peter to pay Paul can always depend on the support of Paul.

Sorry to be a free speech absolutist. (© Elon Musk)

“I have never understood why it is "greed" to want to keep the money you have earned but not greed to want to take somebody else's money.” ― Thomas Sowell

Sorry to be a free speech absolutist. (© Elon Musk)

“I have never understood why it is "greed" to want to keep the money you have earned but not greed to want to take somebody else's money.” ― Thomas Sowell

-

anonymous

Re: Corona en de cijfers

Diegene die vinden dat de maatregelen hier te ver gaan.

Wat verkies je? SItuatie zoals hier of die van Bolivia?

https://www.hln.be/video/mobiel-cremato ... en~p159781

Wat verkies je? SItuatie zoals hier of die van Bolivia?

https://www.hln.be/video/mobiel-cremato ... en~p159781

Re: Corona en de cijfers

Boliviaanse maatregelen met de Belgische rijkdom ^^

Maar het is ook appelen met peren vergelijken

Als je in Bolivia de Belgische maatregelen neemt, dan vermijd je die beelden niet en dan krijg je er nog eens een burgeroorlog bij...

Dus hun aanpak is niet per definitie fout...

Het is gewoon een ander land, met een totaal andere situatie

Maar wij kijken graag met onze Europese bril op naar andere landen en geven dan commentaar

Maar het is ook appelen met peren vergelijken

Als je in Bolivia de Belgische maatregelen neemt, dan vermijd je die beelden niet en dan krijg je er nog eens een burgeroorlog bij...

Dus hun aanpak is niet per definitie fout...

Het is gewoon een ander land, met een totaal andere situatie

Maar wij kijken graag met onze Europese bril op naar andere landen en geven dan commentaar

Re: Corona en de cijfers

Zweden, laatste dagcijfer : 160 besmettingen.CarpeNoctem schreef: ↑4 augustus 2020, 12:36 Ik ga voor de auto die minst pannes heeft op 250.000 km. Want dat is wat er gebeurt, Zweden mikt op de lange termijn.

Wat hebben we in België gezien : dat victorie kraaien bij 40 en 80 + nog veel te vroeg is.

In Thailand is dat de laatste dagen 5 -3 - 1..

Je stijl mag er wezen... De facts zijn toch wel enorm gekleurd en ronduit verkeerd.

Als ik mag kiezen waar ik wil zijn.. dan kies ik voor Thailand maar dat was ook al zo voor Corona.

En dat is dan ineens een keuze tussen veel maatregelen en weinig.

Zweden lijkt mij totaal niet de beste leerling van de klas.

Re: Corona en de cijfers

Ik wil niet per se komen vertellen dat Zweden het slecht deed.

Maar vandaag viel me het cijfer op voor de regio Stockholm.

23.101 besmettingen

2.384 doden.

Mortaliteit van meer dan tien procent (België had slechtere cijfers of komen we in realiteit ongeveer gelijk ?) terwijl dat in andere regio's heel anders was. Daar moet een reden voor zijn. Ze hebben net als ons veel doden in de rusthuizen..

Al lang niet meer gezegd : onze +72.000 besmettingen waar slechts +27000 een gekende uitkomst hebben gekend, officieel, is ook wel een vorm van niet tellen of opvolgen waaraan eens iets gedaan mag worden.

Ons dagelijks cijfer : 858.

Wie is er nog altijd te vinden voor minder maatregelen (retorische vraag) ?

Maar vandaag viel me het cijfer op voor de regio Stockholm.

23.101 besmettingen

2.384 doden.

Mortaliteit van meer dan tien procent (België had slechtere cijfers of komen we in realiteit ongeveer gelijk ?) terwijl dat in andere regio's heel anders was. Daar moet een reden voor zijn. Ze hebben net als ons veel doden in de rusthuizen..

Al lang niet meer gezegd : onze +72.000 besmettingen waar slechts +27000 een gekende uitkomst hebben gekend, officieel, is ook wel een vorm van niet tellen of opvolgen waaraan eens iets gedaan mag worden.

Ons dagelijks cijfer : 858.

Wie is er nog altijd te vinden voor minder maatregelen (retorische vraag) ?

- CarpeNoctem

- Verbannen Gebruiker

- Berichten: 1264

- Lid geworden op: 05 jan 2014

Re: Corona en de cijfers

Voor diegene die niet weten waar onze eerste plaats vandaan komt:

WHEN COVID-19 HIT, MANY ELDERLY WERE LEFT TO DIE

"WHEN COVID-19 HIT, MANY ELDERLY WERE LEFT TO DIE

BRUSSELS — Shirley Doyen was exhausted. The Christalain nursing home, which she ran with her brother in an affluent neighborhood in Brussels, was buckling from Covid-19. Eight residents had died in three weeks. Some staff members had only gowns and goggles from Halloween doctor costumes for protection.

Nor was help coming. Ms. Doyen had begged hospitals to collect her infected residents. They refused. Sometimes she was told to administer morphine and let death come. Once she was told to pray.

Then, in the early morning of April 10, it all got worse.

First, a resident died at 1:20 a.m. Three hours later, another died. At 5:30 a.m., still another. The night nurse had long since given up calling ambulances.

Ms. Doyen arrived after dawn and discovered Addolorata Balducci, 89, in distress from Covid-19. Ms. Balducci’s son, Franco Pacchioli, demanded that paramedics be called and begged them to take his mother to the hospital. Instead, they gave her morphine.

“Your mother will die,” the paramedics responded, Mr. Pacchioli recalled. “That’s it.”

The paramedics left. Eight hours later, Ms. Balducci died.

Thanks for reading The Times.

Subscribe to The Times

Runaway coronavirus infections, medical gear shortages and government inattention are woefully familiar stories in nursing homes around the globe. But Belgium’s response offers a gruesome twist: Paramedics and hospitals sometimes flatly denied care to elderly people, even as hospital beds sat unused.

Weeks earlier, the virus had overwhelmed hospitals in Italy. Determined to prevent that from happening in Belgium, the authorities shunned and all but ignored nursing homes. But while Italian doctors said they were forced to ration care to the elderly because of shortages of space and equipment, Belgium’s hospital system never came under similar strain.

Even at the height of the outbreak in April, when Ms. Balducci was turned away, intensive-care beds were no more than about 55 percent full.

“They wouldn’t accept old people,” Ms. Doyen said. “They had space, and they didn’t want them.”

Belgium now has, by some measures, the world’s highest coronavirus death rate, in part because of nursing homes. More than 5,700 nursing-home residents have died, according to newly published data. During the peak of the crisis, from March through mid-May, residents accounted for two out of every three coronavirus deaths.

Of all the missteps by governments during the coronavirus pandemic, few have had such an immediate and devastating impact as the failure to protect nursing homes. Tens of thousands of older people died — casualties not only of the virus, but of more than a decade of ignored warnings that nursing homes were vulnerable.

Public health officials around the world excluded nursing homes from their pandemic preparedness plans and omitted residents from the mathematical models used to guide their responses.

In recent months, the coronavirus outbreak in the United States has dominated global attention, as the world’s richest nation blundered its way into the world’s largest death toll. Some 40 percent of those fatalities have been linked to long-term-care facilities. But even now, European countries lead the world in per capita deaths, in part because of what happened inside their nursing homes.

Spanish prosecutors are investigating cases in which residents were abandoned to die. In Sweden, overwhelmed emergency doctors have acknowledged turning away elderly patients.

In Britain, the government ordered thousands of older hospital patients — including some with Covid-19 — sent back to nursing homes to make room for an expected crush of virus cases. (Similar policies were in effect in some American states.)

But by fixating on saving their hospitals, European leaders sometimes left nursing-home residents and staff to fend for themselves.

“We thought about it, and we said, ‘Care homes are important,’” Matt Keeling, a British emergency adviser, testified recently. “We thought they were being shielded, and we probably thought that was enough.”

It wasn’t. Only about a third of European nursing homes had infectious-disease teams before the Covid-19 pandemic. Most lacked in-house doctors and many had no arrangements with outside physicians to coordinate care.

Few countries embody this lethally ineffective pandemic response more than Belgium, where government officials excluded nursing-home patients from the testing policy until thousands were already dead. Nursing homes were left waiting for proper masks and gowns. When masks did arrive from the government, they came late and were sometimes defective.

“Tape the masks to the bridge of your nose,” regional health officials advised in one email.

One nursing-home executive, bereft of options, ordered thousands of ponchos after seeing animal-keepers wearing them in a countryside zoo. Another home managed to get 5,000 masks from a staff member’s father in Vietnam. The precious cargo arrived through the embassy’s diplomatic pouch.

Belgian officials say denying care for the elderly was never their policy. But in the absence of a national strategy, and with regional officials bickering about who was in charge, officials now acknowledge that some hospitals and emergency responders relied on vague advice and guidelines to do just that.

The situation was so dire that the charity Médecins Sans Frontières dispatched teams of experts more accustomed to working in war-hardened countries. On March 25, when a team arrived at Val des Fleurs, a public nursing home a few miles from European Union headquarters, they were greeted by the stale smell of disinfectant and an eerie stillness, pierced only by the song of a caged canary.

When the M.S.F. team arrived, both the director and her deputy were sick with Covid-19.

Seventeen people had died there in the past 10 days. There was no protective equipment. Oxygen was running low. Half the staff was infected. Others showed signs of trauma common in disaster zones, a psychologist from the medical charity concluded.

The director and her deputy were sick with Covid-19, and the acting chief collapsed in a chair, crying, as soon as the team met her.

“I never thought I would work with M.S.F. in my own country. That’s crazy. We are a rich country,” said Marine Tondeur, a Belgian nurse who has worked in South Sudan and Haiti.

Ms. Tondeur was horrified at her country’s response.

“I feel a bit ashamed, actually, that we forgot those homes.”

‘Firefighters in Pajamas’

In February, as the coronavirus was taking root in northern Italy, Belgian officials expressed little alarm. Maggie De Block, Belgium’s federal health minister, spent the month playing down the risk. She saw no need to worry about hospital capacity or testing capabilities.

“It isn’t a very aggressive virus. You would have to sneeze in someone’s face to pass it on,” she said on March 3, adding, “If the temperature rises, it will probably disappear.”

Even after the World Health Organization highlighted the importance of creating plans to protect nursing homes, a spokesman for the health authority in Belgium’s Dutch-speaking region said there was no reason to worry.

“The risk of infection is very small for now,” he said.

Yet the warning signs were there. Belgium has one of the world’s largest nursing-home populations per capita, and years of research has shown that respiratory illnesses like Covid-19 are among the most common diseases in such facilities. Data from China demonstrated that the elderly were most at risk from Covid-19.

Government reports as far back as 2006 had called for infectious-disease training for nursing-home doctors and public help to stockpile protective equipment. A separate report in 2009 recommended adding nursing homes to the national pandemic plan. Both proposals went nowhere.

So, at the beginning of March, nursing homes were effectively on their own. Belgium’s internal risk-assessment documents did not even mention nursing homes among the top concerns.

“We have received no specific recommendations from the ministers,” the nursing-home association Femarbel wrote to its members.

Nursing homes around the world operate at the seams of local, regional and national oversight, but Belgium magnifies that problem. Divided by language and perpetually difficult to govern, Belgium has so many layers of bureaucracy that it is sometimes referred to as an administrative lasagna.

The country has not one but nine health ministers, who answer to six parliaments. The federal government takes a coordinating role in a pandemic, but nursing homes are the purview of regional authorities.

So even when officials realized the threat posed by Covid-19, they could not act decisively.

“We needed several weeks to figure out who was responsible,” Pedro Facon, a top federal health official, testified this month.

By the middle of March, with the coronavirus spreading rapidly, regional governments offered nursing homes advice — yet it was unhelpful on key points. Government documents stressed the importance of masks, while simultaneously declaring them all but unavailable.

“There are virtually no masks available on the market,” one document said. Caregivers were advised to reuse masks, withhold them from administrative staff members, and scrounge for gear from nearby hospitals.

And scrounge they did. At the Christalain home, Steve Doyen — the co-owner and Ms. Doyen’s brother — said he found a handful of gowns and goggles through a friend who liked dressing up as a doctor for Halloween.

Worsening the problem, Belgium was unable to test even a fraction of those infected. So the health authorities decided to test severely ill, hospitalized patients. Everyone else was told to recover at home.

That meant leaving contagious people inside crowded, understaffed, underequipped nursing homes.

“We got the impression quite early on that we would take the back seat,” said Lesley Moreels, the director of a public nursing home in Brussels. “We felt that we were going to be firefighters in pajamas.”

Test, Return, Infect

Belgium went into lockdown on March 18. Dozens of nursing-home residents had already died. Three days later, Jacqueline Van Peteghem, a 91-year-old resident at the Christalain home, was sent to UZ Brussel, a nearby hospital, where she was tested for Covid-19. Within days, her test came back positive.

Shirley and Steve Doyen assumed Ms. Van Peteghem would remain hospitalized for treatment and to prevent the disease from spreading to scores of other residents. But her symptoms had stabilized, and Mr. Doyen said that a hospital doctor declared her healthy enough to return home.

So, on March 27, paramedics in hazmat suits delivered Ms. Van Peteghem, on a stretcher, to the door of Christalain.

Mr. Doyen greeted them wearing a surgical mask.

“Is this mask all you have?” the paramedics asked, Mr. Doyen recalled.

“Yes,” he said.

“Good luck,” they responded.

For the next hour, Christalain staff members watched as the paramedics decontaminated themselves and their ambulance. Asked later about the hospital’s policies, the chief executive, Prof. Marc Noppen, said infectious patients were not normally returned to nursing homes but that it may have happened in some cases.

No one can be certain if Ms. Van Peteghem’s return was the reason, but Covid-19 infections in the home increased. Residents began dying. Ms. Van Peteghem, who initially survived the virus, died last month.

The Belgian authorities were aware of such problems, according to internal documents. “Some patients have returned from the hospital infected,” a government emergency committee wrote on March 25. “Several hot spots have been caused this way.”

The committee recommended testing nursing-home residents and establishing locations to house Covid-19 patients who would otherwise be returned to homes.

But national and regional authorities could not agree on those recommendations, and the country remained a hodgepodge of policies.

For another two weeks, even as the government expanded its testing capability, health advisers resisted adding nursing homes to the national testing priority list. They worried that even the newfound capacity would be unable to meet the demand under the broadened criteria, according to documents and government officials.

“The federal government had tests. Hospitals had tests,” said Dr. Emmanuel André, a virologist who was tapped as a top government adviser and who advocated for broader federal testing. “But nursing homes? There were no tests allowed.”

As a stopgap measure, Philippe De Backer, a minister who had been tapped to expand testing, pushed out an initial batch of nursing-home tests in early April. But he and others wanted residents formally added to the testing priority list. Support for that change finally coalesced on April 8. Mr. De Backer dialed into a conference call of the government’s risk-management group — one of many committees that set policy in Belgium.

“You can stop debating,” he said. “We’re testing in care homes.”

When the first results were announced, one in five residents tested positive. By then, more than 2,000 residents had already died.

As the testing debate unfolded in late March and early April, hospitals quietly stopped taking infected patients from nursing homes.

The policy — officially it was just advice — took shape in a series of memos from Belgian geriatric specialists.

“Unnecessary transfers are a risk for ambulance workers and emergency rooms,” read an early memo, signed by the Belgian Society for Gerontology and Geriatrics and two major hospitals.

Extremely frail patients and the terminally ill should receive palliative care and not be hospitalized, the memo said. The document offered a complex flowchart for deciding when to hospitalize nursing-home residents.

The gerontology society says that its advice — drafted in case of an overwhelmed hospital system — was misunderstood. The society is not a government agency, doctors there note, and it never intended to deny hospital care for the elderly.

But that is what happened.

Do Not Admit

On the morning of April 9, Dr. André, the government adviser, was preparing for the daily news briefing when one question, submitted in advance by a journalist, caught him by surprise: Would nursing-home residents soon be allowed to go to the hospital?

“Why is this question coming?” Dr. André remembers thinking. “Yes, of course they can.”

But time and again, nursing-home residents with Covid-19 symptoms were denied hospitalization, even when referred by doctors who had assessed that they might recover.

“The decision not to accept residents in hospitals really shocked me,” said Michel Hanset, a doctor in Brussels who tried in vain to admit several nursing-home patients.

No data exists on how often this happened, but Médecins Sans Frontières says about 30 percent of the homes it worked in during its deployment reported this problem.

Government figures are also telling. During the first weeks of the crisis, nearly two thirds of nursing-home residents’ deaths occurred in hospitals. But as the crisis worsened, and the geriatric memos began circulating, that number plummeted.

At the peak of the outbreak, a mere 14 percent of gravely ill residents made it to hospitals. The rest died in their nursing homes, according to government data compiled by Belgian scientists and released to The New York Times.

It is impossible to know how many deaths were preventable. But hospitals always had space. Even at the peak of the pandemic, 1,100 of the nation’s 2,400 intensive care beds were free, according to Niel Hens, a government adviser and University of Antwerp professor.

“Paramedics had been instructed by their referral hospital not to take patients over a certain age, often 75 but sometimes as low as 65,” Médecins Sans Frontières said in a July report.

Some senior regional and national officials acknowledge this problem.

“I heard from staff in care homes that emergency doctors were arriving, taking residents and then they were sending them back to care homes, saying they could not keep them in the hospital,” Christie Morreale, the top health official in Wallonia, Belgium’s French-speaking region, said in an interview.

Ms. De Block, the national health minister, declined to be interviewed and did not respond to written questions. In interviews, senior hospital doctors defended their policies. They said that nursing-home staff sought hospital care for terminally ill patients who needed to be comforted into death, not dragged to the hospital.

If nursing-home residents were denied admission, they say, it was because a doctor determined that they were unlikely to survive.

“If you think medical treatment is of benefit for that patient, he or she will be hospitalized,” said Professor Noppen, the UZ Brussel executive. “It’s as simple as that.”

Nursing-home administrators are adamant that was not the case.

“At a certain point, there was an implicit age limit,” said Marijke Verboven of Orpea group, which owns 60 homes around Belgium.

Mr. Moreels, whose nursing home, Val des Roses, also had an intervention from a Médecins Sans Frontières team, agreed. “The ambulance wouldn’t take them,” he said. “There was no detailed consultation. They just said ‘Why did you even call us?’”

The Brussels ambulance service denied any policy of refusing to take nursing-home residents to the hospital. Yet even some doctors are skeptical.

“We learned that people from care homes believed it was not even worth calling an ambulance,” said Dr. Charlotte Martin, the chief epidemiologist at Saint-Pierre Hospital in central Brussels. “They should have been the first ones to get in the pipeline. And instead they were just forgotten.”

At the Christalain home, activities resumed this summer and life inched toward something resembling normal. But a shadow remains: 14 residents have been confirmed to have died of Covid-19. Another, devastated and confused from the quarantine, killed herself in April.

Mr. Pacchioli, whose mother died after being refused hospitalization, is haunted by a question. “Maybe it wasn’t too late,” he said. “If she had gone to the hospital, maybe she would have survived.”

The Médecins Sans Frontières teams concluded their nursing-home missions in Belgium in mid-June. Some members returned to developing countries. Others now work in another rich nation in crisis: the United States.

Today, Ms. De Block, Belgium’s national health minister, speaks about the nursing homes as if they were an unfortunate footnote in a story of a successful government response. She notes with pride that Belgium never ran out of hospital beds.

“We took measures at the right moment,” she said in an interview, adding, “We can be proud.”

Reporting was contributed by David Kirkpatrick and Selam Gebrekidan in London, Julia Echikson and Koba Ryckewaert in Brussels, and Christina Anderson in Stockholm.

Matina Stevis-Gridneff is the Brussels correspondent for The New York Times, covering the European Union. She joined The Times after covering East Africa for The Wall Street Journal for five years. @MatinaStevis

Matt Apuzzo is a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter based in Brussels. He has covered law enforcement and security matters for more than a decade and is the co-author of the book “Enemies Within.” @mattapuzzo

A version of this article appears in print on Aug. 9, 2020 of the New York edition with the headline: As Covid Hit, The World Let Its Elderly Die. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe"

WHEN COVID-19 HIT, MANY ELDERLY WERE LEFT TO DIE

"WHEN COVID-19 HIT, MANY ELDERLY WERE LEFT TO DIE

BRUSSELS — Shirley Doyen was exhausted. The Christalain nursing home, which she ran with her brother in an affluent neighborhood in Brussels, was buckling from Covid-19. Eight residents had died in three weeks. Some staff members had only gowns and goggles from Halloween doctor costumes for protection.

Nor was help coming. Ms. Doyen had begged hospitals to collect her infected residents. They refused. Sometimes she was told to administer morphine and let death come. Once she was told to pray.

Then, in the early morning of April 10, it all got worse.

First, a resident died at 1:20 a.m. Three hours later, another died. At 5:30 a.m., still another. The night nurse had long since given up calling ambulances.

Ms. Doyen arrived after dawn and discovered Addolorata Balducci, 89, in distress from Covid-19. Ms. Balducci’s son, Franco Pacchioli, demanded that paramedics be called and begged them to take his mother to the hospital. Instead, they gave her morphine.

“Your mother will die,” the paramedics responded, Mr. Pacchioli recalled. “That’s it.”

The paramedics left. Eight hours later, Ms. Balducci died.

Thanks for reading The Times.

Subscribe to The Times

Runaway coronavirus infections, medical gear shortages and government inattention are woefully familiar stories in nursing homes around the globe. But Belgium’s response offers a gruesome twist: Paramedics and hospitals sometimes flatly denied care to elderly people, even as hospital beds sat unused.

Weeks earlier, the virus had overwhelmed hospitals in Italy. Determined to prevent that from happening in Belgium, the authorities shunned and all but ignored nursing homes. But while Italian doctors said they were forced to ration care to the elderly because of shortages of space and equipment, Belgium’s hospital system never came under similar strain.

Even at the height of the outbreak in April, when Ms. Balducci was turned away, intensive-care beds were no more than about 55 percent full.

“They wouldn’t accept old people,” Ms. Doyen said. “They had space, and they didn’t want them.”

Belgium now has, by some measures, the world’s highest coronavirus death rate, in part because of nursing homes. More than 5,700 nursing-home residents have died, according to newly published data. During the peak of the crisis, from March through mid-May, residents accounted for two out of every three coronavirus deaths.

Of all the missteps by governments during the coronavirus pandemic, few have had such an immediate and devastating impact as the failure to protect nursing homes. Tens of thousands of older people died — casualties not only of the virus, but of more than a decade of ignored warnings that nursing homes were vulnerable.

Public health officials around the world excluded nursing homes from their pandemic preparedness plans and omitted residents from the mathematical models used to guide their responses.

In recent months, the coronavirus outbreak in the United States has dominated global attention, as the world’s richest nation blundered its way into the world’s largest death toll. Some 40 percent of those fatalities have been linked to long-term-care facilities. But even now, European countries lead the world in per capita deaths, in part because of what happened inside their nursing homes.

Spanish prosecutors are investigating cases in which residents were abandoned to die. In Sweden, overwhelmed emergency doctors have acknowledged turning away elderly patients.

In Britain, the government ordered thousands of older hospital patients — including some with Covid-19 — sent back to nursing homes to make room for an expected crush of virus cases. (Similar policies were in effect in some American states.)

But by fixating on saving their hospitals, European leaders sometimes left nursing-home residents and staff to fend for themselves.

“We thought about it, and we said, ‘Care homes are important,’” Matt Keeling, a British emergency adviser, testified recently. “We thought they were being shielded, and we probably thought that was enough.”

It wasn’t. Only about a third of European nursing homes had infectious-disease teams before the Covid-19 pandemic. Most lacked in-house doctors and many had no arrangements with outside physicians to coordinate care.

Few countries embody this lethally ineffective pandemic response more than Belgium, where government officials excluded nursing-home patients from the testing policy until thousands were already dead. Nursing homes were left waiting for proper masks and gowns. When masks did arrive from the government, they came late and were sometimes defective.

“Tape the masks to the bridge of your nose,” regional health officials advised in one email.

One nursing-home executive, bereft of options, ordered thousands of ponchos after seeing animal-keepers wearing them in a countryside zoo. Another home managed to get 5,000 masks from a staff member’s father in Vietnam. The precious cargo arrived through the embassy’s diplomatic pouch.

Belgian officials say denying care for the elderly was never their policy. But in the absence of a national strategy, and with regional officials bickering about who was in charge, officials now acknowledge that some hospitals and emergency responders relied on vague advice and guidelines to do just that.

The situation was so dire that the charity Médecins Sans Frontières dispatched teams of experts more accustomed to working in war-hardened countries. On March 25, when a team arrived at Val des Fleurs, a public nursing home a few miles from European Union headquarters, they were greeted by the stale smell of disinfectant and an eerie stillness, pierced only by the song of a caged canary.

When the M.S.F. team arrived, both the director and her deputy were sick with Covid-19.

Seventeen people had died there in the past 10 days. There was no protective equipment. Oxygen was running low. Half the staff was infected. Others showed signs of trauma common in disaster zones, a psychologist from the medical charity concluded.

The director and her deputy were sick with Covid-19, and the acting chief collapsed in a chair, crying, as soon as the team met her.

“I never thought I would work with M.S.F. in my own country. That’s crazy. We are a rich country,” said Marine Tondeur, a Belgian nurse who has worked in South Sudan and Haiti.

Ms. Tondeur was horrified at her country’s response.

“I feel a bit ashamed, actually, that we forgot those homes.”

‘Firefighters in Pajamas’

In February, as the coronavirus was taking root in northern Italy, Belgian officials expressed little alarm. Maggie De Block, Belgium’s federal health minister, spent the month playing down the risk. She saw no need to worry about hospital capacity or testing capabilities.

“It isn’t a very aggressive virus. You would have to sneeze in someone’s face to pass it on,” she said on March 3, adding, “If the temperature rises, it will probably disappear.”

Even after the World Health Organization highlighted the importance of creating plans to protect nursing homes, a spokesman for the health authority in Belgium’s Dutch-speaking region said there was no reason to worry.

“The risk of infection is very small for now,” he said.

Yet the warning signs were there. Belgium has one of the world’s largest nursing-home populations per capita, and years of research has shown that respiratory illnesses like Covid-19 are among the most common diseases in such facilities. Data from China demonstrated that the elderly were most at risk from Covid-19.

Government reports as far back as 2006 had called for infectious-disease training for nursing-home doctors and public help to stockpile protective equipment. A separate report in 2009 recommended adding nursing homes to the national pandemic plan. Both proposals went nowhere.

So, at the beginning of March, nursing homes were effectively on their own. Belgium’s internal risk-assessment documents did not even mention nursing homes among the top concerns.

“We have received no specific recommendations from the ministers,” the nursing-home association Femarbel wrote to its members.

Nursing homes around the world operate at the seams of local, regional and national oversight, but Belgium magnifies that problem. Divided by language and perpetually difficult to govern, Belgium has so many layers of bureaucracy that it is sometimes referred to as an administrative lasagna.

The country has not one but nine health ministers, who answer to six parliaments. The federal government takes a coordinating role in a pandemic, but nursing homes are the purview of regional authorities.

So even when officials realized the threat posed by Covid-19, they could not act decisively.

“We needed several weeks to figure out who was responsible,” Pedro Facon, a top federal health official, testified this month.

By the middle of March, with the coronavirus spreading rapidly, regional governments offered nursing homes advice — yet it was unhelpful on key points. Government documents stressed the importance of masks, while simultaneously declaring them all but unavailable.

“There are virtually no masks available on the market,” one document said. Caregivers were advised to reuse masks, withhold them from administrative staff members, and scrounge for gear from nearby hospitals.

And scrounge they did. At the Christalain home, Steve Doyen — the co-owner and Ms. Doyen’s brother — said he found a handful of gowns and goggles through a friend who liked dressing up as a doctor for Halloween.

Worsening the problem, Belgium was unable to test even a fraction of those infected. So the health authorities decided to test severely ill, hospitalized patients. Everyone else was told to recover at home.

That meant leaving contagious people inside crowded, understaffed, underequipped nursing homes.

“We got the impression quite early on that we would take the back seat,” said Lesley Moreels, the director of a public nursing home in Brussels. “We felt that we were going to be firefighters in pajamas.”

Test, Return, Infect

Belgium went into lockdown on March 18. Dozens of nursing-home residents had already died. Three days later, Jacqueline Van Peteghem, a 91-year-old resident at the Christalain home, was sent to UZ Brussel, a nearby hospital, where she was tested for Covid-19. Within days, her test came back positive.

Shirley and Steve Doyen assumed Ms. Van Peteghem would remain hospitalized for treatment and to prevent the disease from spreading to scores of other residents. But her symptoms had stabilized, and Mr. Doyen said that a hospital doctor declared her healthy enough to return home.

So, on March 27, paramedics in hazmat suits delivered Ms. Van Peteghem, on a stretcher, to the door of Christalain.

Mr. Doyen greeted them wearing a surgical mask.

“Is this mask all you have?” the paramedics asked, Mr. Doyen recalled.

“Yes,” he said.

“Good luck,” they responded.

For the next hour, Christalain staff members watched as the paramedics decontaminated themselves and their ambulance. Asked later about the hospital’s policies, the chief executive, Prof. Marc Noppen, said infectious patients were not normally returned to nursing homes but that it may have happened in some cases.

No one can be certain if Ms. Van Peteghem’s return was the reason, but Covid-19 infections in the home increased. Residents began dying. Ms. Van Peteghem, who initially survived the virus, died last month.

The Belgian authorities were aware of such problems, according to internal documents. “Some patients have returned from the hospital infected,” a government emergency committee wrote on March 25. “Several hot spots have been caused this way.”

The committee recommended testing nursing-home residents and establishing locations to house Covid-19 patients who would otherwise be returned to homes.

But national and regional authorities could not agree on those recommendations, and the country remained a hodgepodge of policies.

For another two weeks, even as the government expanded its testing capability, health advisers resisted adding nursing homes to the national testing priority list. They worried that even the newfound capacity would be unable to meet the demand under the broadened criteria, according to documents and government officials.

“The federal government had tests. Hospitals had tests,” said Dr. Emmanuel André, a virologist who was tapped as a top government adviser and who advocated for broader federal testing. “But nursing homes? There were no tests allowed.”

As a stopgap measure, Philippe De Backer, a minister who had been tapped to expand testing, pushed out an initial batch of nursing-home tests in early April. But he and others wanted residents formally added to the testing priority list. Support for that change finally coalesced on April 8. Mr. De Backer dialed into a conference call of the government’s risk-management group — one of many committees that set policy in Belgium.

“You can stop debating,” he said. “We’re testing in care homes.”

When the first results were announced, one in five residents tested positive. By then, more than 2,000 residents had already died.

As the testing debate unfolded in late March and early April, hospitals quietly stopped taking infected patients from nursing homes.

The policy — officially it was just advice — took shape in a series of memos from Belgian geriatric specialists.

“Unnecessary transfers are a risk for ambulance workers and emergency rooms,” read an early memo, signed by the Belgian Society for Gerontology and Geriatrics and two major hospitals.

Extremely frail patients and the terminally ill should receive palliative care and not be hospitalized, the memo said. The document offered a complex flowchart for deciding when to hospitalize nursing-home residents.

The gerontology society says that its advice — drafted in case of an overwhelmed hospital system — was misunderstood. The society is not a government agency, doctors there note, and it never intended to deny hospital care for the elderly.

But that is what happened.

Do Not Admit

On the morning of April 9, Dr. André, the government adviser, was preparing for the daily news briefing when one question, submitted in advance by a journalist, caught him by surprise: Would nursing-home residents soon be allowed to go to the hospital?

“Why is this question coming?” Dr. André remembers thinking. “Yes, of course they can.”

But time and again, nursing-home residents with Covid-19 symptoms were denied hospitalization, even when referred by doctors who had assessed that they might recover.

“The decision not to accept residents in hospitals really shocked me,” said Michel Hanset, a doctor in Brussels who tried in vain to admit several nursing-home patients.

No data exists on how often this happened, but Médecins Sans Frontières says about 30 percent of the homes it worked in during its deployment reported this problem.

Government figures are also telling. During the first weeks of the crisis, nearly two thirds of nursing-home residents’ deaths occurred in hospitals. But as the crisis worsened, and the geriatric memos began circulating, that number plummeted.

At the peak of the outbreak, a mere 14 percent of gravely ill residents made it to hospitals. The rest died in their nursing homes, according to government data compiled by Belgian scientists and released to The New York Times.

It is impossible to know how many deaths were preventable. But hospitals always had space. Even at the peak of the pandemic, 1,100 of the nation’s 2,400 intensive care beds were free, according to Niel Hens, a government adviser and University of Antwerp professor.

“Paramedics had been instructed by their referral hospital not to take patients over a certain age, often 75 but sometimes as low as 65,” Médecins Sans Frontières said in a July report.

Some senior regional and national officials acknowledge this problem.

“I heard from staff in care homes that emergency doctors were arriving, taking residents and then they were sending them back to care homes, saying they could not keep them in the hospital,” Christie Morreale, the top health official in Wallonia, Belgium’s French-speaking region, said in an interview.

Ms. De Block, the national health minister, declined to be interviewed and did not respond to written questions. In interviews, senior hospital doctors defended their policies. They said that nursing-home staff sought hospital care for terminally ill patients who needed to be comforted into death, not dragged to the hospital.

If nursing-home residents were denied admission, they say, it was because a doctor determined that they were unlikely to survive.

“If you think medical treatment is of benefit for that patient, he or she will be hospitalized,” said Professor Noppen, the UZ Brussel executive. “It’s as simple as that.”

Nursing-home administrators are adamant that was not the case.

“At a certain point, there was an implicit age limit,” said Marijke Verboven of Orpea group, which owns 60 homes around Belgium.

Mr. Moreels, whose nursing home, Val des Roses, also had an intervention from a Médecins Sans Frontières team, agreed. “The ambulance wouldn’t take them,” he said. “There was no detailed consultation. They just said ‘Why did you even call us?’”

The Brussels ambulance service denied any policy of refusing to take nursing-home residents to the hospital. Yet even some doctors are skeptical.

“We learned that people from care homes believed it was not even worth calling an ambulance,” said Dr. Charlotte Martin, the chief epidemiologist at Saint-Pierre Hospital in central Brussels. “They should have been the first ones to get in the pipeline. And instead they were just forgotten.”

At the Christalain home, activities resumed this summer and life inched toward something resembling normal. But a shadow remains: 14 residents have been confirmed to have died of Covid-19. Another, devastated and confused from the quarantine, killed herself in April.

Mr. Pacchioli, whose mother died after being refused hospitalization, is haunted by a question. “Maybe it wasn’t too late,” he said. “If she had gone to the hospital, maybe she would have survived.”

The Médecins Sans Frontières teams concluded their nursing-home missions in Belgium in mid-June. Some members returned to developing countries. Others now work in another rich nation in crisis: the United States.

Today, Ms. De Block, Belgium’s national health minister, speaks about the nursing homes as if they were an unfortunate footnote in a story of a successful government response. She notes with pride that Belgium never ran out of hospital beds.

“We took measures at the right moment,” she said in an interview, adding, “We can be proud.”

Reporting was contributed by David Kirkpatrick and Selam Gebrekidan in London, Julia Echikson and Koba Ryckewaert in Brussels, and Christina Anderson in Stockholm.

Matina Stevis-Gridneff is the Brussels correspondent for The New York Times, covering the European Union. She joined The Times after covering East Africa for The Wall Street Journal for five years. @MatinaStevis

Matt Apuzzo is a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter based in Brussels. He has covered law enforcement and security matters for more than a decade and is the co-author of the book “Enemies Within.” @mattapuzzo

A version of this article appears in print on Aug. 9, 2020 of the New York edition with the headline: As Covid Hit, The World Let Its Elderly Die. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe"

A government that robs Peter to pay Paul can always depend on the support of Paul.

Sorry to be a free speech absolutist. (© Elon Musk)

“I have never understood why it is "greed" to want to keep the money you have earned but not greed to want to take somebody else's money.” ― Thomas Sowell

Sorry to be a free speech absolutist. (© Elon Musk)

“I have never understood why it is "greed" to want to keep the money you have earned but not greed to want to take somebody else's money.” ― Thomas Sowell

Re: Corona en de cijfers

Weer een oogopener, dat artikel in The Times. Tijd voor een grondige en grote schoonmaak (we zijn al wat decennia te laat). Laten we niet opnieuw vallen voor lege woorden en loze beloften, het touw niet sparen om de boel terug op orde te stellen en die augiasstal uit te mesten op alle niveaus.

The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. Thomas Jefferson.

Freedom is not free.

Freedom is not free.

Re: Corona en de cijfers

Ik heb me deze namiddag eens bezig gehouden met cijfers te verzamelen om het corona plaatje van de hele wereld te reduceren tot een kleinschalig beter vatbare cijfermatige analogie en tenslotte een analogie die een illustratie is van het verschil tussen gevaar en aanpak gevaar.

Wereldbevolking 2020 08 09: 7700 miljoen. https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wereldbevolking

Wereld doden (door gemiddelde leeftijd en totaal bevolking)

Jaarlijks : 56 miljoen https://www.medindia.net/patients/calcu ... -clock.asp

Maandelijks: 4,68 miljoen https://www.medindia.net/patients/calcu ... -clock.asp

Dagelijks: 153425, maal 198 dagen = 30,38 miljoen

Wereld corona 198 dagen https://www.worldometers.info/coronavir ... eath-toll/

Doden 0,73 miljoen + genezen 12,75 miljoen + ziek 6,3 miljoen

Doden dagelijks: 0,73 miljoen / 198 = 3687

Verhouding wereldbevolking / doden corona = 7700 miljoen / 0,73 miljoen = 10548 (om voor onderstaande analogie op ronde 1 dode door corona uit te komen)

Verhouding wereld doden 198 dagen / doden corona 198 dagen = 30,38 miljoen / 0,73 miljoen = 41,6

Analogie met een gemeente met 10548 inwoners, op basis van bovenstaande cijfers, 198 dagen periode, stand van zaken:

- 1 dode in een WZC met een aantal bestaande medische problemen, laatste druppel zijnde corona

- (153425 / 3687) - 1 = 40,6 doden door andere oorzaken.

- 6,3 miljoen / 0,73 miljoen = 8,6 liggen in een ziekenhuis met corona.

- 12,75 miljoen / 0,73 miljoen = 17 genezen van corona

Het gemeentebestuur van de 10548, met die ene corona dode en 17 + 8,6 = 25,6 besmette als opgegeven reden:

1. dwingt alle niet-voedingswinkels tot sluiten, aankondiging veroorzakende een hele week drommen hamsterende mensen in supermarkten, en daarna 3 weken geen kat (hamsters kopen immers voor een tijd niet meer)

2. dwingt 1.50 meter afstand te houden.

3. dwingt een vod / filter voor mond en neus te dragen in alle winkels en zelfs in hele binnensteden en winkelstraten.

4. dwingt onrechtstreeks (limiet klanten per m2 winkelruimte) winkelkar of korf gebruik af, als een middeleeuwse telmethode met als kost een agent>vakantiejobber>gepensioneerde aan de ingang en het telkens moeten ontsmetten van kar of korf, enkel maar besmettingsrisico verhogende.

5. dwingt alle bedrijven die 2. en 3. niet kunnen handhaven tot sluiten.

6. straft particuliere overtreders met boetes van 250 euro en bedrijfsmatige met boete van 3-4 keer dat.

7. dwingt identificatie en registratie bij cafe's, restaurants

8. moedigt in propaganda spotjes het verklikken van medeburgers aan, die dan in quarantaine worden gestampt.

9. geeft de minste ruimte nodig hebbende voetgangers de halve baanruimte en stampt auto's en fietsers in twee richtingen bij elkaar op de andere helft.

10. versmalt doorgangen, zet hindernissen.

11. verbiedt autogebruik, en veroorzaakt drommen werkloos gemaakten die de zo al te smalle fietspaden bomvol maken.

12. politie rijdt traag als nazi antennewagens ter opsporing van verzetsradios rond door lege binnensteden speurende naar corona-misdadigers.

Enz.

Voor die 1 corona dode en 25,6 besmetten in 198 dagen, in een gemeente met 10548 luitjes.

Stel eens een voetbalwedstrijd in een stad. De rechtermiddenvelder wordt in zijn rechterwijsvinger gestoken door een bij.

De scheidsrechter last de rest van de wedstrijd af en legt de rest van het voetbalseizoen stil. De spelers en de toeschouwers worden afgevoerd naar een quarantainedorp.

Niemand in stad mag het huis uit, elke opgeslotene moet binnen een imkerpak dragen en insectenverdelgingsfirma's spuiten de stad onder, om de bijen tot de laatste uitgeroeid te krijgen.

Zolang nog 1 bij leeft, wordt de toestand gehandhaafd.

Elke uur wordt een aantal doden en een aantal besmetten gerapporteerd op alle visuele media.

Herinner beeldje 1 van dit voetbalverhaal.

Dit was science fiction noch WOII noch USSR. Dit is de wereld nu, anno 2020.

Hier in Belgie zijn er officieel een 10000 corona doden over 198 dagen. Ergens in junu las ik 70% in WZC, en mensen met al een rijtje serieuzere medische problemen.

En elk jaar zijn er een 110000-115000 doden door gemiddelde leeftijd en bevolkingsgrootte.

De conclusie is dat het niet het virus was dat samenleving en economie stil legde, maar de overheid.

Wereldbevolking 2020 08 09: 7700 miljoen. https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wereldbevolking

Wereld doden (door gemiddelde leeftijd en totaal bevolking)

Jaarlijks : 56 miljoen https://www.medindia.net/patients/calcu ... -clock.asp

Maandelijks: 4,68 miljoen https://www.medindia.net/patients/calcu ... -clock.asp

Dagelijks: 153425, maal 198 dagen = 30,38 miljoen

Wereld corona 198 dagen https://www.worldometers.info/coronavir ... eath-toll/

Doden 0,73 miljoen + genezen 12,75 miljoen + ziek 6,3 miljoen

Doden dagelijks: 0,73 miljoen / 198 = 3687

Verhouding wereldbevolking / doden corona = 7700 miljoen / 0,73 miljoen = 10548 (om voor onderstaande analogie op ronde 1 dode door corona uit te komen)

Verhouding wereld doden 198 dagen / doden corona 198 dagen = 30,38 miljoen / 0,73 miljoen = 41,6

Analogie met een gemeente met 10548 inwoners, op basis van bovenstaande cijfers, 198 dagen periode, stand van zaken:

- 1 dode in een WZC met een aantal bestaande medische problemen, laatste druppel zijnde corona

- (153425 / 3687) - 1 = 40,6 doden door andere oorzaken.

- 6,3 miljoen / 0,73 miljoen = 8,6 liggen in een ziekenhuis met corona.

- 12,75 miljoen / 0,73 miljoen = 17 genezen van corona

Het gemeentebestuur van de 10548, met die ene corona dode en 17 + 8,6 = 25,6 besmette als opgegeven reden:

1. dwingt alle niet-voedingswinkels tot sluiten, aankondiging veroorzakende een hele week drommen hamsterende mensen in supermarkten, en daarna 3 weken geen kat (hamsters kopen immers voor een tijd niet meer)

2. dwingt 1.50 meter afstand te houden.

3. dwingt een vod / filter voor mond en neus te dragen in alle winkels en zelfs in hele binnensteden en winkelstraten.

4. dwingt onrechtstreeks (limiet klanten per m2 winkelruimte) winkelkar of korf gebruik af, als een middeleeuwse telmethode met als kost een agent>vakantiejobber>gepensioneerde aan de ingang en het telkens moeten ontsmetten van kar of korf, enkel maar besmettingsrisico verhogende.

5. dwingt alle bedrijven die 2. en 3. niet kunnen handhaven tot sluiten.

6. straft particuliere overtreders met boetes van 250 euro en bedrijfsmatige met boete van 3-4 keer dat.

7. dwingt identificatie en registratie bij cafe's, restaurants

8. moedigt in propaganda spotjes het verklikken van medeburgers aan, die dan in quarantaine worden gestampt.

9. geeft de minste ruimte nodig hebbende voetgangers de halve baanruimte en stampt auto's en fietsers in twee richtingen bij elkaar op de andere helft.

10. versmalt doorgangen, zet hindernissen.

11. verbiedt autogebruik, en veroorzaakt drommen werkloos gemaakten die de zo al te smalle fietspaden bomvol maken.

12. politie rijdt traag als nazi antennewagens ter opsporing van verzetsradios rond door lege binnensteden speurende naar corona-misdadigers.

Enz.

Voor die 1 corona dode en 25,6 besmetten in 198 dagen, in een gemeente met 10548 luitjes.

Stel eens een voetbalwedstrijd in een stad. De rechtermiddenvelder wordt in zijn rechterwijsvinger gestoken door een bij.

De scheidsrechter last de rest van de wedstrijd af en legt de rest van het voetbalseizoen stil. De spelers en de toeschouwers worden afgevoerd naar een quarantainedorp.

Niemand in stad mag het huis uit, elke opgeslotene moet binnen een imkerpak dragen en insectenverdelgingsfirma's spuiten de stad onder, om de bijen tot de laatste uitgeroeid te krijgen.

Zolang nog 1 bij leeft, wordt de toestand gehandhaafd.

Elke uur wordt een aantal doden en een aantal besmetten gerapporteerd op alle visuele media.

Herinner beeldje 1 van dit voetbalverhaal.

Dit was science fiction noch WOII noch USSR. Dit is de wereld nu, anno 2020.

Hier in Belgie zijn er officieel een 10000 corona doden over 198 dagen. Ergens in junu las ik 70% in WZC, en mensen met al een rijtje serieuzere medische problemen.

En elk jaar zijn er een 110000-115000 doden door gemiddelde leeftijd en bevolkingsgrootte.

De conclusie is dat het niet het virus was dat samenleving en economie stil legde, maar de overheid.

http://achterdesamenleving.nl/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Het-meest-gevaarlijke-bijgeloof-11.pdf

-

anonymous

Re: Corona en de cijfers

Er zijn nog wel wat sektes beschikbaar waar je ongetwijfeld een publiek zal vinden voor je geraaskal maar ik heb het na een zin of 10 opgegeven.